Revisiting implant controversies

Loading protocols revisited

The US perspective

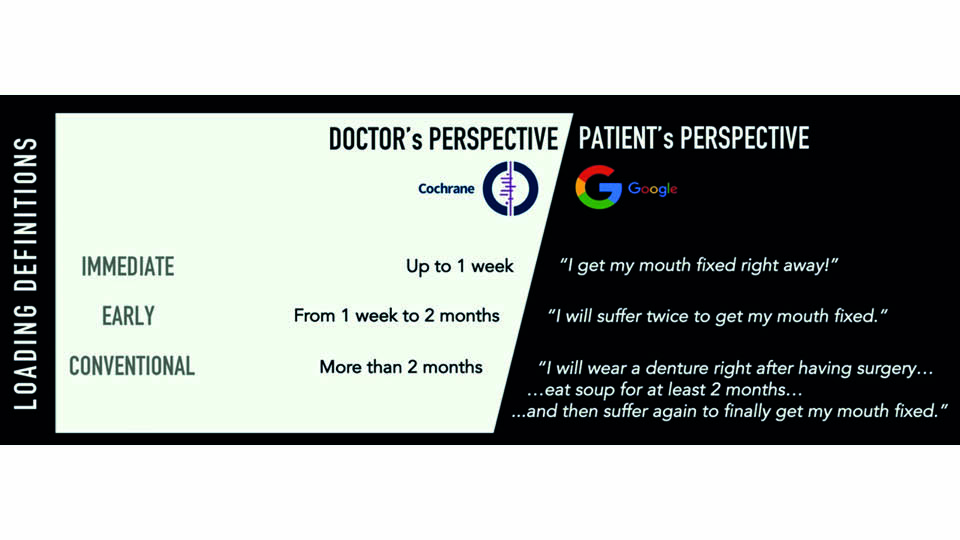

The definitions of loading protocols have not been modified since 2007 (Esposito et al., 2007):

- conventional loading: two months or more from implant placement

- early loading: between one week and two months

- immediate loading: within one week of implant placement

Immediate loading protocol is predictable

At the 6th International Team for Implantology (ITI) consensus conference in 2018, the protocol for immediate placement plus immediate restoration/loading was found to be clinically well documented with a mean survival rate of 98%. No significant differences were found in outcomes for full-arch fixed protheses supported by less than five implants compared to five or more implants, nor for when implants were angulated or axially positioned (Morton et al., 2018).

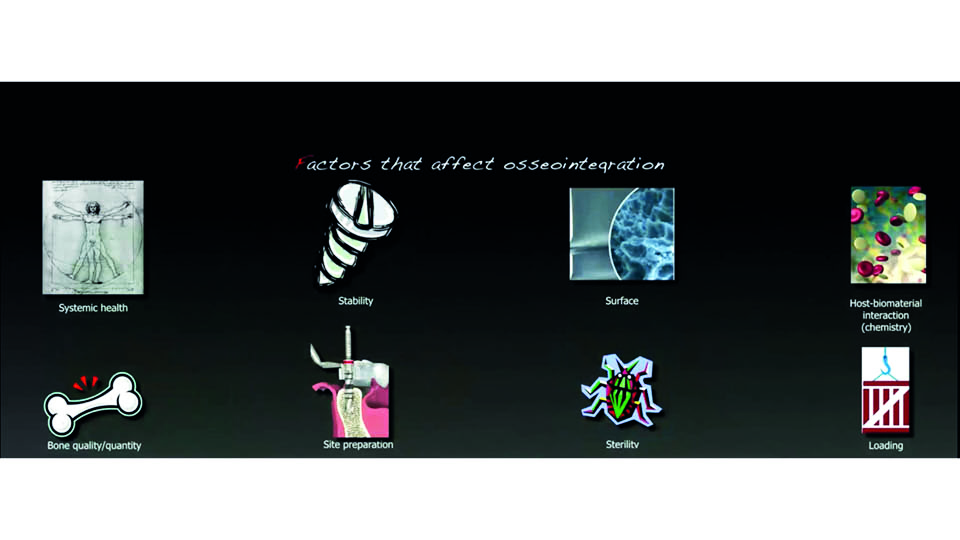

The load does not affect osseointegration unless the implant moves

At the time of placement, implant stability depends only on the friction between the surface and the bone. This primary stability is gradually lost over time due to osteoclastic activity, while a secondary stability increases as new bone forms (fig 1).

It is well known that implant stability is a pre-requisite for osseointegration. Load would be harmful if it caused mobility, as this would disrupt the bone-implant interface. Load does not affect the process of completing secondary stability, provided that proper primary stability is achieved at the time of placement and occlusal forces are under control (fig 2).

A clinically proven protocol

According to the speaker’s own protocol published in 2001 (Ganeles et al., 2001), successful treatment needs a number of diverse factors to be taken into account:

- adequate number and distribution of implants

- adequate quantity and quality of bone

- a rigid provisional restoration

- control of occlusal forces

- patient cooperation

- whole team integration (surgeon, laboratory, restorative) to have the treatment done in a short space of time

This protocol is more predictable in the mandible; with some small modifications it is also suitable in the maxilla. Revisiting the protocol now, the speaker said that some more factors should be considered.

What has changed today, in 2019, with respect to what was described in 2001?

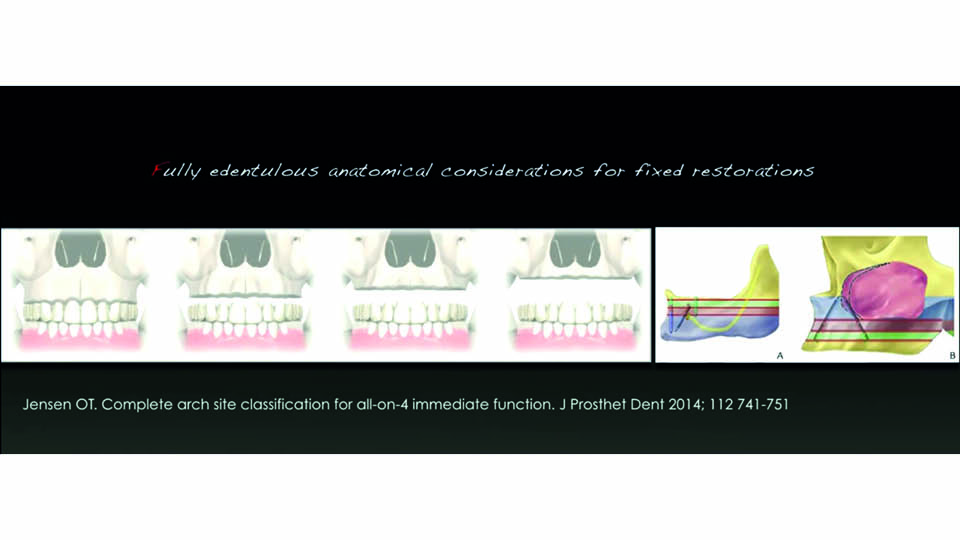

A new classification for assessing both the timing of implant placement and loading combinations has been proposed, to optimise treatment selection (Morton et al., 2018). Hard and soft tissue deficiencies must both be considered because different types of bone resorption demand different types of solutions. There are also various classifications for evaluating the difficulty of implant placement, the type of prothesis needed and assessing whether immediate loading is suitable (Jensen et al., 2014) (fig 3).

An overnight provisional

In immediate loading approaches, the speaker proposed the immediate placement of a functional provisional (overnight provisional) made directly in the office. This would let the patient go home with teeth while their long-term provisional is fabricated in the laboratory.

The speaker described the procedure as follows: the previous diagnostic wax-up is duplicated to make two thermoplastic shells with a vacuum machine. Thus, the ideal position of the restoration is captured and any potential need to increase or reduce hard/soft tissues can be pre-planned. After implant placement in the planned positions, an impression and an occlusal record are taken with one of the two vacuum splints. The other splint is used to make the overnight provisional. This is made by filling the splint with self-curing resin once it is located exactly with a provisional abutment on the most stable implant. Meanwhile, the long-term provisional is manufactured in the laboratory.

Guide for the occlusal design of complete restorations with immediate loading

This guide is based on periodontal prostheses and was pioneered by Morton Amsterdam in the fifties. Its purpose is to minimise lateral movements, to protect periodontally compromised teeth.

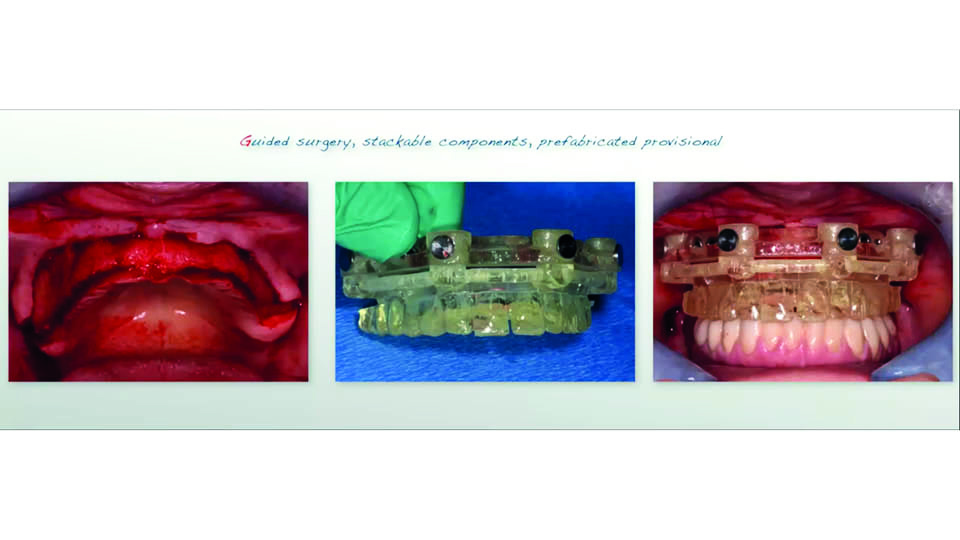

Nowadays, digital tools are used to register occlusal schemes. Occlusal parameters can be integrated into digital workflows to have surgery pre-planned and the provisional pre-fabricated before surgery. So, it is no longer necessary to make the overnight provisional chairside (fig 4–5).

Immediate loading is not appropriate for inexperienced clinicians

Immediate loading has documented benefits, but it is a complex surgical and prosthodontic procedure. It is associated with higher risks of complications or failures than other loading options. Therefore, the speaker stated that it should only be performed by clinicians with the prerequisite clinical skill and experience. Immediate contour management and grafting may optimise aesthetic outcomes when significant augmentation or site development is not needed.

Presentation figures

Fig 1: Primary and secondary stability

Fig 2: Factors affecting osseointegration

Fig 3: Therapeutic classification

Fig 4: Pre-fabricated provisional

Fig 5: The pre-fabricated provisional

References:

Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Willings M, Coulthard P, Worthington HV. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: different times for loading dental implants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18;(2):CD003878 2007.

Ganeles J, Rosenberg MM, Holt RL, Reichman LH. Immediate Loading of Implants with Fixed Restorations in the Completely Edentulous Mandible: Report of 27 Patients from a Private Practice. Int J Oral MAxillofac Implants 2001;16:418-26.

Jensen OT. Complete arch site classification for all-on-4 immediate function. J Prosthet Dent 2014;112:741-51.

Morton D, Gallucci G, Lin WS, Pjetursson B, Polido W, Roehling S, et al. Group 2 ITI Consensus Report: Prosthodontic and implant dentistry. Clin Oral Impl Res. 2018;29(Suppl 16):215-23.

The European perspective

The speaker highlighted the importance of a patient-centred perspective: adapting the technique to the patient, not vice versa. To this end, we need to know what the patient wants (Dierens et al., 2009). Patients generally want immediacy, but the practitioner wants predictability. The point is: how can we combine the two requests to achieve an ideal rehabilitation? (fig 6)

Immediate loading is highly predictable in full-arch fixed restorations

There have been a number of systematic reviews on this topic (nine since 2007, three of which were from 2019) which support the predictability of immediate loading compared to other loading options. But all studies emphasise higher risks with immediate loading.

The higher reported risk could be due to the inclusion of removable and partial prostheses in the studies. With total fixed restorations, it can be assumed that immediate loading is highly predictable (probably because the stability of the full-arch limits micromotion) (Sanz-Sánchez et al., 2015). Osseointegration does not require an absolute absence of load, but does require minimal micromotion in the bone-implant interface (Szmukler-Moncler et al., 1998).

Immediate loading is not a predictable option for every patient: there are critical factors

It has been shown that immediate loading is more predictable in the mandible than in the maxilla. Further, tobacco, periodontitis, diabetes, bruxism are all risk factors whose presence should make us reconsider the suitability of immediate loading approaches (Caramês et al., 2006). The speaker outlined some critical factors involved in the immediate loading approach which should be carefully assessed (Gapski et al., 2003):

- related to the patient: healing capacity, anatomical considerations

- related to surgery: primary stability, surgical technique

- related to occlusion: cross-arch stabilisation, force and intensity vectors, prosthesis design and material

- related to the implant: number and distribution, design and length, surface

There is no one solution that suits all patients. Different levels of atrophy require different rehabilitation approaches. Each patient is different, therefore in each case the technique must be tailored to fit the minute details of each patient.

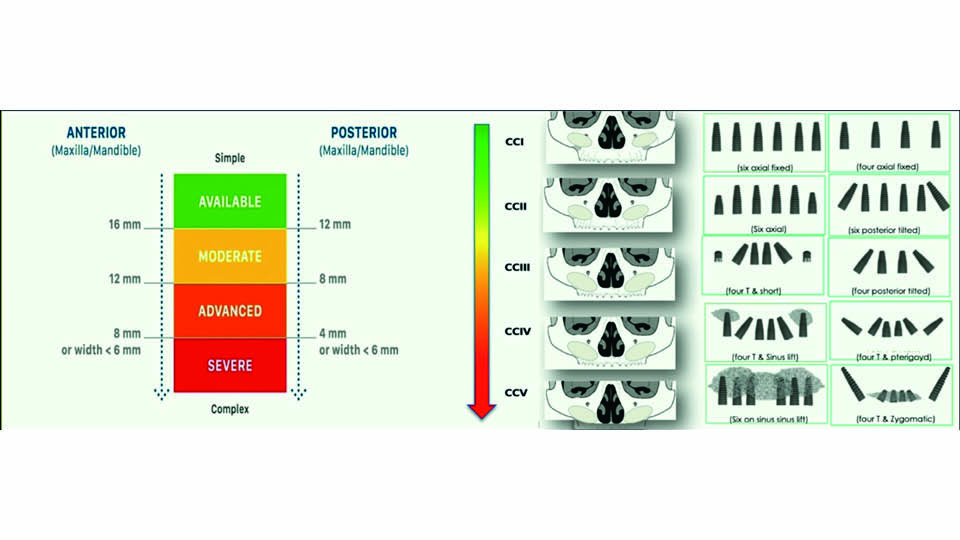

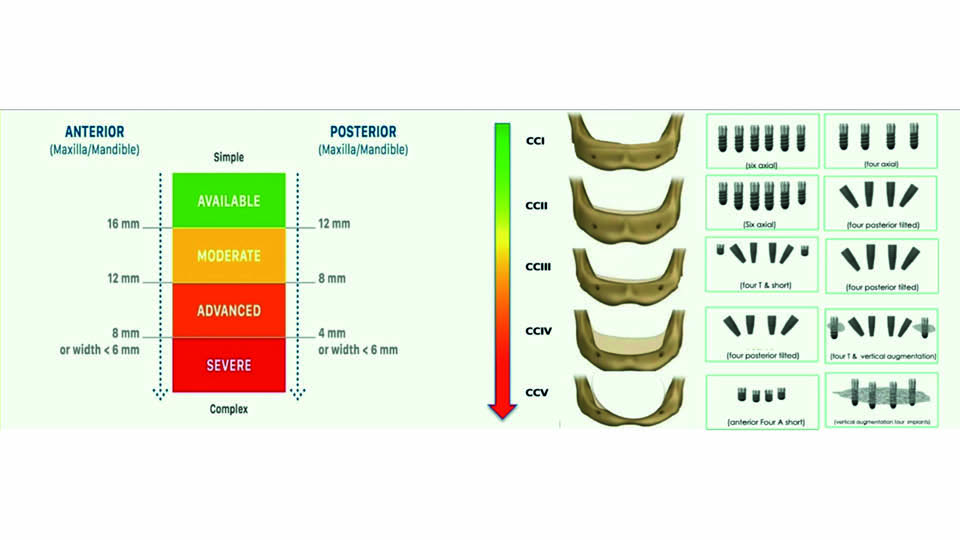

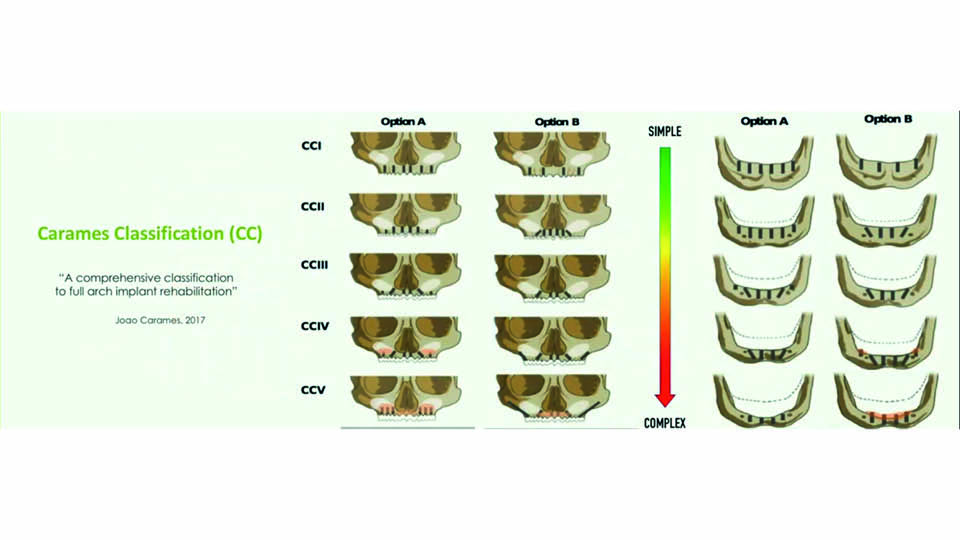

The speaker proposed a classification system to help decision making (Caramês et al., 2017) (fig 7–8). This is based on the degree of bone atrophy both in anterior and posterior areas. Cases are classified in five categories: I, II, III, IV and V, for mandible and for maxilla. For each category, a treatment option (A) is proposed and an alternative option (B), depending on the particular preferences of each patient.

In some atrophic cases, anatomy needs to be restored before we can proceed with implant placement. Sometimes, tilted implants may provide a ‘graftless’ solution for patients who prioritise speed. An ongoing retrospective study on 3,795 implants with up to 7-year follow-up has found cumulative survival rates (CSR) of 95–99% in the maxilla, and 98–100% in the mandible (fig 9).

For definitive restorations, the speaker recommended monolithic zirconia with ceramic veneers on anterior teeth to improve aesthetic appearance (Caramês et al., 2019).

Presentation figures

Fig 6: Two perspectives to be combined

Fig 7: Classification to help decision making. Maxilla

Fig 8: Classification to help decision making. Mandible

Fig 9: The Carames Classification

References:

Caramês J, Pragosa A, Sousa S, Chen A, Ascenso J. Assessment of host-related risk factors in immediate loading: a 3-year retrospective analysis. Clin Oral Implant Res 2006;17(4): Abstracts of the 15th Annual Meeting EAO. Zurich. Poster 121.

Caramês J. A comprehensive classification to full arch implant rehabilitation. Submitted to BMC Oral Health, 2017;2.

Caramês J, Marques D, Malta Barbosa J, Moreira A, Crispim P, Chen A. Full-arch implant-supported rehabilitations: A prospective study comparing porcelain-veneered zirconia frameworks to monolithic zirconia. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2019;30(1):68-78.

Dierens M, Collaert B, Deschepper E, Browaeys H, Klinge B, De Bruyn H. Patient centered outcome of immediately loaded implants in the rehabilitation of fully edentulous jaws. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2009;20(10):1070-7.

Gapski R, Wang HL, Mascarenhas P, Lang NP. Critical review of immediate implant loading. Clin Oral Implant Res 2003;14(5):515-27.

Sanz-Sánchez I, Sanz‐Martín I, Figuero E, Sanz M. Clinical efficacy of immediate implant loading protocols compared to conventional loading depending on the type of the restoration: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2015;26(8): 964-82.

Szmukler-Moncler S, Salama H, Reingewirtz Y, Dubruille JH. Timing of loading and effect of micromotion on bone-dental implant interface: review of experimental literature. J Biomed Mater Res 1998;43(2):192-203.